Your essential UGC NET guide covering eligibility criteria, exam pattern, Paper I and II syllabus, application process, preparation tips, and career benefits after qualifying. This article is written by Neeli Neelay Shah, Senior Legal Content Writer at LawSikho.

If you are considering an academic career in India, UGC NET is likely the most important examination on your radar. Conducted by the National Testing Agency (NTA) twice a year, this national-level test determines your eligibility for Assistant Professor positions in universities and colleges, and awards the prestigious Junior Research Fellowship (JRF) to top performers seeking funded doctoral research. Whether you are a final year postgraduate student exploring career options or a working professional planning to switch to academia, this guide gives you everything you need to understand UGC NET without drowning in information overload.

Educational Qualification

The basic requirement for UGC NET is a Master’s degree from a recognized university in a subject relevant to your chosen Paper II. General and EWS category candidates need at least 55% marks in their postgraduate degree, while reserved category candidates (SC, ST, OBC-NCL, PwD, Third Gender) need 50% marks. If you are currently in your final year of Master’s, you can still apply and appear for the examination, though you must complete your degree with the required percentage before the deadline specified in the notification.

The 55% or 50% calculation is based on aggregate marks across all semesters of your postgraduate programme. Distance education and open university degrees are accepted as long as the institution holds proper UGC recognition. Foreign degrees are also valid if they have been equivalence-certified by the Association of Indian Universities and for Law students it needs to be validated by the Bar Council of India. This inclusive approach ensures that qualified candidates from diverse educational pathways can pursue academic careers.

Your subject choice for Paper II should align with your postgraduate specialization. For instance, if you completed your Master’s in Law, you would typically choose Law (Subject Code 41) for Paper II. However, some candidates with interdisciplinary backgrounds may choose subjects based on their stronger preparation area, provided they have equivalent knowledge of the complete syllabus.

Age Limit for JRF and Assistant Professor

Here is where UGC NET becomes particularly attractive: there is no upper age limit for Assistant Professor eligibility. Whether you are 28 or 48, if you meet the educational qualifications, you can appear for the exam and become eligible to teach at universities and colleges across India. This policy recognizes that valuable teaching experience and subject expertise can develop at any stage of life, and opening academic careers to mature candidates enriches the higher education system.

However, for the Junior Research Fellowship component, the maximum age is 30 years for General category candidates as on the first day of January of the examination year. Reserved categories OBC-NCL, SC, ST, PwD receive a 5-year relaxation, making the limit 35 years. Women candidates across all categories get an additional 5-year relaxation. Other relaxations exist for LLM holders (+3 years), army officers and research experience (up to 5 years).

This age limit applies only to JRF; even if you exceed the JRF age limit, you can still qualify for Assistant Professor eligibility and PhD admission eligibility. Many candidates above 30 years of age successfully clear UGC NET and build fulfilling teaching careers without the JRF component. The fellowship is attractive for its financial support during doctoral research, but it is not the only valuable outcome of clearing this examination.

Four-Year Undergraduate Programme (FYUP) Under NEP 2020

The National Education Policy 2020 has introduced a significant new eligibility pathway that reflects the restructured higher education system in India. Candidates who complete a four-year undergraduate programme with research components and score at least 75% marks are now eligible for UGC NET-JRF, even without a traditional two-year Master’s degree. This provision opens doors for students from multidisciplinary undergraduate programmes to pursue academic careers directly after their bachelor’s degree.

This pathway is particularly relevant for students enrolled in institutions implementing NEP 2020’s multidisciplinary education framework. The four-year programme typically includes a research project or dissertation component in the final year, which prepares students for the research aptitude tested in UGC NET Paper I. As more universities adopt this structure, expect to see increasing numbers of candidates using this eligibility route.

However, candidates using this pathway should note that their UGC NET Paper II subject choice should align with their major area of study during the undergraduate programme. The 75% marks requirement is also higher than the Master’s degree pathway, reflecting the expectation of strong academic performance to compensate for shorter formal education duration.

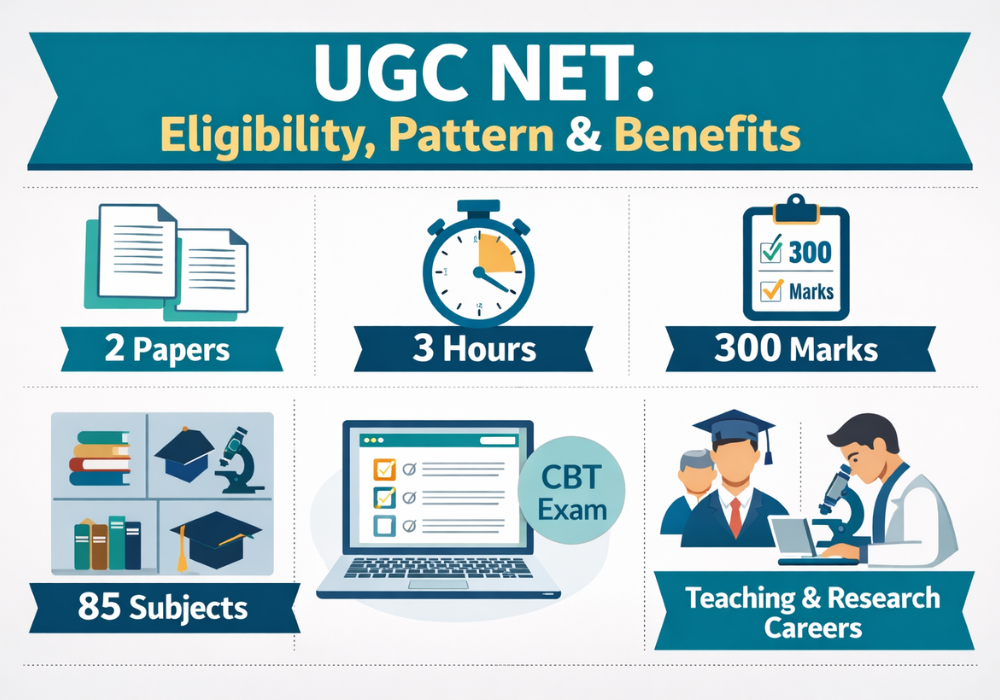

Complete UGC NET Exam Structure: Duration, Mode, and Question Distribution

UGC NET is conducted as a Computer-Based Test (CBT) in a single session of 3 hours (180 minutes). Both Paper I and Paper II are administered together without any break, and you answer a total of 150 questions worth 300 marks. The examination is held at designated test centres across India, and you can select up to four preferred cities during the application process. The NTA allots centres based on availability, so popular cities may not always be guaranteed.

The best news for test-takers is that there is no negative marking in UGC NET. Every correct answer earns you 2 marks, while wrong or unattempted questions simply carry zero marks. This means you should never leave any question blank, even if you are completely unsure about the answer. Even educated guesses have potential value since there is no penalty for incorrect responses. Attempt every single question before time runs out, using elimination techniques for questions where you can narrow down options.

The CBT interface allows you to navigate freely between Paper I and Paper II during the examination. You can mark questions for review and return to them later, switch between papers as per your comfort, and see a question palette showing your progress. Familiarizing yourself with this interface through NTA’s free mock tests available on the official portal is highly recommended before your actual examination day.

Paper I: Teaching and Research Aptitude (50 Questions, 100 Marks)

UGC NET Paper I is the common paper that every UGC NET aspirant must clear, regardless of their chosen subject. It tests your general aptitude for teaching and research careers through 50 multiple-choice questions worth 100 marks. While there is no fixed time allocation between papers, most successful candidates spend approximately 50-60 minutes on Paper I and reserve 120-130 minutes for the more extensive Paper II.

The UGC NET Paper I syllabus covers 10 comprehensive units designed to evaluate competencies essential for academic careers. Unit 1 (Teaching Aptitude) covers teaching levels, learner characteristics, and teaching methods. Unit 2 (Research Methodology) examines research types, designs, sampling, and ethics. Unit 3 (Reading Comprehension) tests analytical reading through passages. Unit 4 (Communication) covers verbal and non-verbal communication skills. Unit 5 (Mathematical Reasoning) tests numerical aptitude through series, percentages, and calculations. Unit 6 (Logical Reasoning) includes syllogisms, analogies, and deductive reasoning. Unit 7 (Data Interpretation) involves tables, charts, and graphs. Unit 8 (ICT) covers digital initiatives and technology in education. Unit 9 (Environment) examines sustainable development and environmental policies. Unit 10 (Higher Education System) tests knowledge of NEP 2020, UGC regulations, and academic reforms.

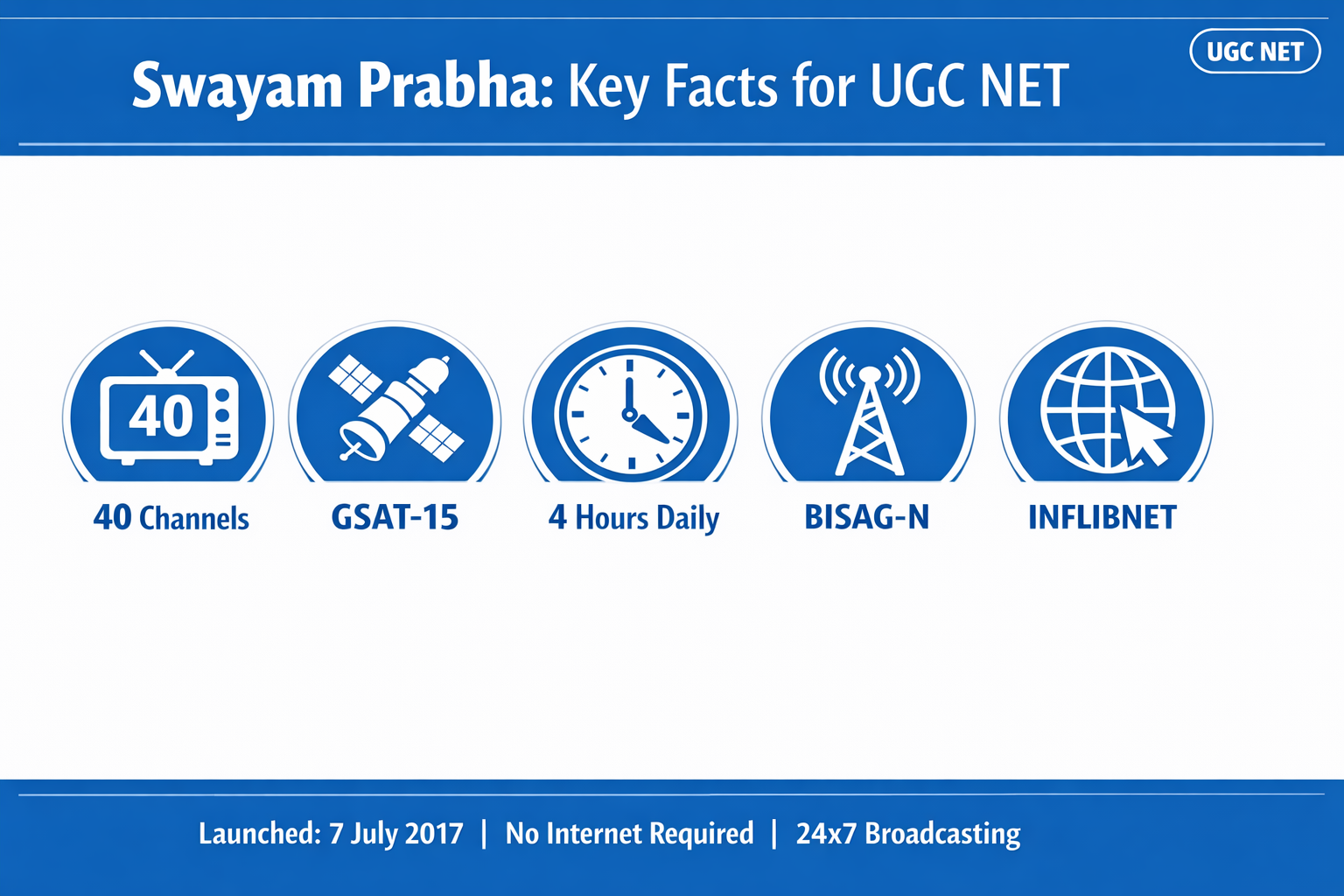

Based on previous year analysis, question distribution across units shows some consistent patterns. Teaching Aptitude and Research Methodology together contribute around 10-12 questions and form the conceptual foundation. Logical Reasoning and Data Interpretation are high-scoring units with 8-10 questions featuring predictable patterns that improve significantly with practice. ICT and Higher Education System questions often test current awareness about digital initiatives like SWAYAM and Swayam Prabha, Digital India, and education policies like NEP 2020. Understanding unit-wise weightage helps you allocate preparation time strategically for maximum impact.

UGC NET Paper II: Subject-Specific Paper (100 Questions, 200 Marks)

Paper II evaluates your in-depth knowledge of your chosen subject through 100 questions worth 200 marks. Since it carries double the weightage of Paper I, your Paper II performance largely determines your final ranking and qualification status. A strong Paper II score can compensate for an average Paper I, but the reverse is rarely true. This is where your postgraduate education and subject expertise truly come into play.

NTA offers 85 subjects for Paper II, spanning humanities, social sciences, sciences, languages, and professional disciplines. Popular high-competition subjects include English Literature, Political Science, Commerce, Education, History, Economics, Sociology, and Law. Your subject choice should align with your postgraduate specialization since questions test Master’s level knowledge across the complete syllabus. Some candidates choose subjects slightly different from their exact PG degree if they have equivalent knowledge, but this requires careful consideration of the syllabus overlap and your preparation strength.

Each Paper II subject has a detailed syllabus divided into 8-10 units covering the breadth of that discipline. The syllabus generally mirrors postgraduate curriculum content and includes both foundational theories and contemporary developments in the field. For instance, Law Paper II covers 10 units spanning Jurisprudence, Constitutional and Administrative Law, International Law and International Humanitarian Law, Criminal Law, Torts and Consumer Protection, Commercial Law, Family Law, Environmental and Human Rights Law, IPR and IT Law, and Comparative Public Law. Commerce Paper II spans Business Environment, Accounting and Auditing, Business Economics, Business Finance, Statistics and Research Methods, Management and HRM, Banking, Marketing, Legal Aspects, and Taxation. Understanding your subject’s unit structure helps you plan systematic preparation.

Marking Scheme and Qualifying Criteria

The marking scheme is refreshingly straightforward: +2 marks for every correct answer, zero marks for incorrect or unattempted questions. With 150 questions totaling 300 marks (Paper I: 50 questions for 100 marks; Paper II: 100 questions for 200 marks), your aggregate score across both papers determines your qualification status. There are no separate qualifying thresholds for individual papers; only the combined aggregate matters.

General and EWS category candidates need minimum 40% aggregate (120 marks out of 300) to qualify for Assistant Professor eligibility. Reserved category candidates (SC, ST, OBC-NCL, PwD, Third Gender) need 35% aggregate (105 marks out of 300). Meeting these minimum thresholds is necessary but not sufficient for actual qualification, as the final cut-off depends on competition levels and varies each session based on candidate performance and available positions.

For JRF, you need to score among the top performers nationally in your subject. The JRF cut-off is always significantly higher than the Assistant Professor cut-off, typically by 20-30 marks depending on the subject and session difficulty. JRF is awarded to a limited number of top scorers based on merit and available fellowship slots, making it considerably more competitive than Assistant Professor eligibility alone.

Paper I Syllabus: 10 Units

Units 1 and 2 form the conceptual foundation of Paper I and are essential for understanding academic work. Unit 1: Teaching Aptitude forms the conceptual foundation of your future teaching career. This unit covers the nature, objectives, characteristics, and basic requirements of teaching at different levels. You need to understand the three levels of teaching: Memory level (where students simply recall information), Understanding level (where students comprehend and explain concepts), and Reflective level (where students analyze, evaluate, and create new ideas). The unit also covers learner characteristics including how age, motivation, prior knowledge, and learning styles affect the learning process. Various teaching methods like lecture, discussion, demonstration, and project-based learning are tested, along with their advantages and limitations.

Unit 2: Research Aptitude evaluates your understanding of the research process from problem identification to conclusion. This unit covers types of research including fundamental research (pure research aimed at expanding knowledge), applied research (solving practical problems), and action research (improving specific practices). You should understand the differences between qualitative research, quantitative research, and mixed-methods approaches. Key concepts include variables (independent, dependent, intervening), sampling methods (probability and non-probability), hypothesis formulation, research ethics (informed consent, confidentiality, plagiarism), and thesis writing. Your postgraduate dissertation experience provides a practical foundation for this unit.

Unit 3: Reading Comprehension tests your ability to understand, analyze, and draw inferences from written passages. This unit typically presents one or more passages of 300-500 words followed by 5-6 questions. Passages cover topics from social sciences, humanities, science and technology, or current affairs. Question types include direct factual questions (answers explicitly stated in the passage), inference-based questions (drawing logical conclusions), vocabulary questions (meaning of words in context), and questions about the author’s tone, purpose, or main argument. The strategy is to read questions first, then scan the passage for relevant answers.

Unit 4: Communication covers the nature and characteristics of communication essential for effective teaching. You need to understand the basic communication model: sender, message, channel, receiver, feedback, and noise. The unit distinguishes between verbal communication (spoken and written words) and non-verbal communication (body language, gestures, facial expressions, eye contact). Different levels of communication including intrapersonal, interpersonal, group, and mass communication are covered. Classroom communication skills, barriers to effective communication (physical, psychological, semantic, cultural), and methods to overcome these barriers are frequently tested topics.

Unit 5: Mathematical Reasoning tests your numerical aptitude through number series, percentages, ratios, and basic calculations. Number series questions present sequences following hidden patterns where you must identify the next or missing number. Patterns can involve addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, squares, cubes, or combinations. Percentage questions test calculating percentages, percentage change, and converting between fractions, decimals, and percentages. This unit rewards practice, and learning mental math shortcuts significantly improves your speed and accuracy during the examination.

Unit 6: Logical Reasoning is a high-scoring unit testing your ability to think systematically and draw valid conclusions. Syllogisms are logical arguments where conclusions are drawn from two given statements, and Venn diagrams help visualize these relationships quickly. Analogies test your ability to identify relationships between pairs of concepts (synonyms, antonyms, part-whole, cause-effect, tool-user relationships). Understanding deductive reasoning (general to specific, conclusions necessarily true) versus inductive reasoning (specific to general, conclusions probable) is important. Common logical fallacies including hasty generalization, circular reasoning, and false cause are also covered.

Unit 7: Data Interpretation presents data in tables, bar graphs, line graphs, and pie charts, requiring you to analyze, compare, and draw conclusions. Questions typically involve calculating percentages, ratios, averages, or growth rates from given data. You may need to compare performance across categories or time periods, identify trends, or find maximum/minimum values. The key strategy is reading questions first to understand what information you need, then looking at the data selectively. Approximation skills are valuable since exact calculations are often unnecessary when answer options are sufficiently spread apart.

Unit 8: Information and Communication Technology (ICT) tests your familiarity with computer basics, internet technologies, and digital initiatives. The Digital India initiative and its key pillars (broadband highways, universal mobile connectivity, e-governance, e-kranti) are frequently tested. E-governance models (G2C, G2B, G2G, G2E) and DigiLocker appear regularly. Cyber security concepts including malware, phishing, hacking, and protective measures are important. ICT in education covers e-learning platforms, MOOCs, SWAYAM, NPTEL, virtual classrooms, and concepts like blended learning and flipped classroom.

Unit 9: People, Development, and Environment covers sustainable development, environmental issues, and the relationship between human activities and the natural environment. Sustainable development (meeting present needs without compromising future generations’ ability) and its three pillars (economic, social, environmental sustainability) are core concepts. The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) adopted in 2015 with 17 goals for 2030 are frequently tested. Environmental legislation including Environment Protection Act 1986, Wildlife Protection Act 1972, and Air and Water Pollution Acts are covered. International agreements like the Paris Agreement, Kyoto Protocol, and Convention on Biological Diversity are important topics.

Unit 10: Higher Education System in India tests your understanding of how higher education is structured and governed in India. The National Education Policy 2020 is a landmark reform document with key provisions including multidisciplinary universities, flexible curriculum with multiple entry-exit options, Academic Bank of Credits, and four-year undergraduate programmes. The University Grants Commission (UGC) functions as the primary regulatory body, and you should understand its roles in coordinating standards, providing grants, and framing regulations. NAAC accreditation (evaluating institutions on seven criteria with grades from A++ to C) and NIRF ranking parameters are important contemporary topics that appear regularly in questions.

Paper II Syllabus: Subject-Specific Coverage

Paper II syllabus is structured around postgraduate-level content divided into 8-10 units depending on the subject, with each unit covering a major domain within the discipline. The depth of coverage mirrors what you would study during a Master’s programme, including both foundational theories and contemporary developments. For Law, the 10 units comprehensively cover Jurisprudence (schools of thought, legal concepts), Constitutional and Administrative Law (fundamental rights, federalism, judicial review), Public International Law and International Humanitarian Law, Law of Crimes (general principles, specific offences under new criminal laws), Torts and Consumer Protection, Commercial Law (contracts, company law, negotiable instruments), Family Law (personal laws across communities), Environmental and Human Rights Law, IPR and IT Law, and Comparative Public Law examining different governance systems.

Commerce Paper II similarly spans 10 units covering the business and commerce discipline comprehensively. Business Environment and International Business examines globalisation, trade policies, and business ethics. Accounting and Auditing (the highest-weightage unit with 12-15 questions) covers financial, cost, and management accounting plus auditing standards. Business Economics includes demand-supply analysis, market structures, and macroeconomic concepts. Business Finance covers capital budgeting, capital structure theories, and working capital management. Statistics and Research Methods tests quantitative techniques and research design. Business Management and HRM examines management theories and HR functions. Banking and Financial Institutions covers RBI, monetary policy, and financial markets. Marketing Management includes consumer behaviour and digital marketing. Legal Aspects covers commercial legislation, and Taxation addresses income tax and corporate tax planning.

The official subject-wise syllabus PDFs are available for download on the UGC NET Online portal in both English and Hindi. Syllabi are periodically updated to reflect current academic developments in respective fields, so ensure you have the latest version and check for any recent modifications announced through NTA notifications.

Paper I: Prepare for Teaching and Research Aptitude

Paper I preparation should begin with understanding each unit’s content, weightage, and question patterns. Teaching Aptitude and Research Methodology require conceptual clarity since questions test understanding of principles rather than mere factual recall. Create summary notes for key theories, their proponents, and distinguishing characteristics. Flashcards work well for matching questions that ask you to connect theories with theorists or concepts with definitions.

Logical Reasoning and Mathematical Reasoning improve dramatically with daily practice. Dedicate 30-45 minutes daily to solving reasoning problems, focusing on speed and accuracy. For syllogisms, master the Venn diagram approach that allows quick visualization of statement relationships. For number series, learn to recognize common patterns (addition, multiplication, squares, cubes, alternating operations) through extensive practice. Data Interpretation similarly rewards regular practice with tables and graphs from previous year papers.

For units like ICT and Higher Education System, maintain a current affairs file with recent policy announcements, digital initiatives, and education reforms. NEP 2020 provisions appear frequently, so read the policy document’s key highlights including multidisciplinary education, Academic Bank of Credits, four-year undergraduate programmes, and regulatory reforms. Environment questions often reference Sustainable Development Goals and international agreements, which can be prepared through concise summaries rather than extensive reading. Subscribe to education news sources or follow UGC and Ministry of Education social media for updates on recent developments.

Paper II: Leverage Your Academic Background

Your postgraduate coursework provides a strong foundation for Paper II preparation, and recognizing this can save significant preparation time. Map your Master’s syllabus systematically against the UGC NET syllabus to identify areas already covered during your degree versus those needing fresh study. For topics you studied during your PG, revision from your existing notes and previous year question practice may suffice rather than starting from scratch with new textbooks.

Focus preparation time proportionate to unit weightage based on previous year paper analysis. In Commerce, Accounting and Auditing contributes 12-15 questions (24-30 marks) while smaller units like Business Environment may have 6-8 questions. In Law, Constitutional Law and Jurisprudence are heavily weighted compared to units like Comparative Public Law. Prioritize high-weightage units for thorough preparation while ensuring basic coverage of all topics to avoid leaving any unit completely unprepared.

Create subject-specific notes as you study rather than just reading passively. Active note-making significantly improves retention and provides quick revision material during the final weeks. Mind maps work exceptionally well for interconnected concepts, helping you visualize relationships and recall information during the examination. Include key case laws (for Law), important theorists and their contributions, formulas (for Commerce numericals), and potential MCQ areas in your notes.

Using Previous Year Papers and Mock Tests Smartly

Previous year papers are your most valuable preparation resource, more useful than any textbook or coaching material. They reveal actual question patterns, difficulty levels, topic emphasis, and question framing styles that you will encounter in the examination. Many questions or their close variations repeat across sessions, making PYQ practice directly scoring. Solve at least 5 years of papers thoroughly, analyzing not just correct answers but also understanding why other options are incorrect.

Begin full-length mock tests approximately 6-8 weeks before the examination date. Simulate actual exam conditions with 3-hour timed sessions without breaks, using the CBT format if possible. Analyze each mock test thoroughly to identify weak areas, track your progress over time, and refine your time management strategy. Note patterns in your mistakes: are they conceptual gaps, careless errors, or time management issues? Address each type differently. Aim for 15-20 full-length mock tests before the actual examination to build stamina and exam temperament. Additionally, many coaching platforms and publishers offer subject-specific mock tests. The key is consistent practice with honest analysis rather than simply accumulating test numbers without learning from mistakes.

The application process is entirely online through the NTA portal at ugcnet.nta.ac.in. The process begins with registration, where you provide basic details including your name (exactly as it appears on official documents), date of birth, mobile number, and email address. Upon successful registration, the system generates a unique application number and password that you must save securely, as these credentials are required for all subsequent interactions including application completion, admit card download, and result checking.

After registration, log in to complete the full application form with detailed personal information, educational qualifications, and examination preferences. Personal details include your complete address, identification information, and category certificates if applicable. Educational details require information about your qualifying degree including university name, year of passing, subjects studied, and percentage obtained. Ensure complete accuracy in these details as discrepancies can lead to application rejection or certificate cancellation after qualification.

Document uploads require careful attention to exact specifications mentioned in the Information Bulletin. Your photograph must be a recent passport-sized colour image with white or light background, in JPEG format between 10-200 KB, taken within the last 3 months. Your signature should be in running handwriting (not block letters) with black ink on white paper, in JPEG format between 4-30 KB. Reserved category candidates must upload valid category certificates in the prescribed format. PwD candidates require disability certificates from authorized medical boards specifying at least 40% disability. Rejection due to document specification violations is common, so verify requirements carefully before uploading.

Examination preferences include selecting your Paper II subject (which cannot be changed after submission), preferred examination cities (up to four choices), and medium of examination (English or Hindi for most subjects). Subject selection is particularly critical since it determines your entire Paper II and cannot be modified even during the correction window. Choose carefully after confirming the subject code from the official Information Bulletin matches your intended subject.

Application Fee

The application fee structure for UGC NET is category-based to ensure accessibility across economic backgrounds. For UGC NET Exam, General/Unreserved candidates pay ₹1,150, OBC-NCL candidates pay ₹600, and SC/ST/PwD/Third Gender candidates pay ₹325. The fee is non-refundable under any circumstances once paid, so ensure you meet all eligibility criteria and have decided firmly on your subject before completing payment.

Payment can be made through multiple online modes including credit cards, debit cards, net banking, UPI, and digital wallets. The payment gateway is secure with instant confirmation. Keep your device charged and ensure stable internet connectivity during the payment process to avoid transaction failures. After successful payment, download and save the payment confirmation receipt immediately as proof of completed application.

UGC NET follows the Government of India’s reservation policy for cut-off determination and JRF allocation. The reservation percentages are: SC (15%), ST (7.5%), OBC-NCL (27%), and EWS (10%). PwD candidates receive 5% horizontal reservation across all categories, meaning a PwD candidate belonging to SC category benefits from both SC vertical reservation and PwD horizontal reservation. These reservations apply primarily to JRF award and merit ranking, ensuring equitable representation in research fellowships across social categories.

For qualification, reserved category candidates benefit from relaxed minimum qualifying percentages (35% aggregate instead of 40%) and separate category-wise cut-offs. This means candidates compete primarily within their category pools for determining merit positions. Candidates must possess valid category certificates issued by competent authorities to avail reservation benefits. OBC-NCL candidates must ensure their certificates specifically include the non-creamy layer clause and are valid for the current financial year. False category claims result in disqualification and potential legal consequences.

UGC NET Result and Answer Key

UGC NET results are typically declared 6-8 weeks after the examination concludes, though this timeline can vary based on administrative factors. The NTA announces results through official notifications on its website and sends SMS and email alerts to registered contact details. Results include your raw score, qualifying status (JRF qualified, Assistant Professor eligible, PhD admission eligible, or Not Qualified), and category-wise rank for JRF qualifiers.

Before final results, NTA releases provisional answer keys along with recorded responses showing your attempted answers. This transparency allows you to calculate your approximate score and compare your responses with official answers. If you believe any answer key is incorrect based on authentic sources, you can challenge it through the online grievance system by paying Rs. 200 per question challenged. Expert committees review all challenges, and final answer keys are prepared after considering valid objections. Successful challenges result in revised answer keys benefiting all affected candidates, and your challenge fee is refunded if your objection is accepted.

UGC NET Scorecard

The scorecard displays comprehensive information including your marks in Paper I and Paper II separately, total aggregate marks, your category, qualifying status, and all-India rank if you qualify for JRF. The scorecard also mentions the validity period of your qualification and can be downloaded from the NTA website for up to one year after result declaration.

UGC NET Cut-Off

Cut-offs vary substantially by subject based on candidate numbers, competition intensity, and paper difficulty. Popular subjects like Commerce, English, Education, and Political Science have higher cut-offs due to large candidate pools competing for limited positions. Niche subjects may have relatively lower cut-offs but also fewer available positions and fellowships.

For June 2025, Commerce JRF cut-off was approximately 224 marks for General category, while Assistant Professor eligibility required around 194 marks. Law cut-offs typically fall in the moderate range, with JRF cut-offs between 180-200 marks for General category depending on the session. These figures vary each cycle, so treat them as indicative benchmarks rather than fixed targets.

Setting your target 15-20 marks above the previous year’s cut-off for your subject is a prudent strategy that provides a safety margin. Analyze your specific subject’s cut-off history rather than relying on general cut-off figures, and track your mock test performance against these benchmarks throughout your preparation.

Certificate Download and Validity

After result declaration, qualified candidates can download their e-certificates from the NTA website. The e-certificate is digitally signed and verifiable through the NTA verification portal, eliminating the need for physical copies in most recruitment processes. The certificate contains your name, photograph, roll number, subject, qualifying status (JRF/Assistant Professor/PhD admission), and date of qualification. Recruiters can verify certificate authenticity online using the certificate number provided.

The Assistant Professor eligibility certificate is valid for lifetime once you qualify. There is no expiry date, and you can use this qualification for university and college faculty recruitment throughout your career. However, for JRF, the fellowship award must be availed within a specified period from the result declaration date, typically three years. If you do not join a PhD programme and activate your JRF within this validity period, the fellowship offer lapses, though your Assistant Professor eligibility remains intact.

After qualifying, your next steps depend on your career goals. For Assistant Professor positions, start monitoring university and college recruitment notifications through employment news, institutional websites, and UGC’s job portal. Prepare for interviews that typically test subject knowledge, teaching demonstration skills, and research aptitude. For JRF recipients, identify universities and research supervisors in your area of interest, apply for PhD admission (NET qualifiers are often exempt from entrance tests), and complete the JRF activation process through the UGC portal after PhD enrollment to start receiving your monthly fellowship stipend.

Qualifying UGC NET opens multiple rewarding career pathways in academia and research. The most direct benefit is eligibility for Assistant Professor positions in universities and colleges across India. With UGC NET qualification, you can apply for teaching positions in central universities, state universities, deemed universities, and affiliated colleges. The starting salary for Assistant Professors under the 7th Pay Commission is approximately ₹57,700 per month (Level 10), with additional allowances like DA, HRA, and academic grade pay bringing the total compensation to ₹70,000-90,000 depending on location and institution type.

For top performers, the Junior Research Fellowship provides substantial financial support for doctoral research. JRF recipients receive a monthly stipend of ₹37,000 for the first two years, increasing to ₹42,000 per month from the third year onwards upon elevation to Senior Research Fellow (SRF) status. Additionally, JRF scholars receive House Rent Allowance (8-24% depending on city category) and an annual contingency grant for books, travel, and research expenses. This fellowship allows you to pursue a PhD without financial constraints, focusing entirely on your research work.

Beyond teaching and research, UGC NET qualification enhances your profile for various academic and administrative roles. Many research positions in government organizations, think tanks, and policy institutes prefer or require NET qualification. Educational content development roles, academic consultancy, and positions in regulatory bodies like UGC, NAAC, and AICTE often list NET as a desirable qualification. The examination also serves as validation of your subject expertise, which can be valuable for career transitions into education technology, publishing, and academic administration.

The PhD admission benefit is particularly valuable: UGC NET qualifiers are exempt from university entrance tests in most institutions, proceeding directly to interviews for doctoral admission. Some universities give significant weightage (up to 70%) to NET scores in their PhD selection process. This streamlined pathway saves preparation time for multiple entrance examinations and demonstrates your research aptitude to potential supervisors. Even if you do not plan an immediate PhD, having this option available provides career flexibility.

UGC NET is your gateway to a fulfilling academic career, whether you aspire to shape young minds as a professor or contribute to knowledge creation as a researcher. The examination is challenging but entirely conquerable with systematic preparation and strategic approach. Remember the key takeaways: meet the eligibility requirements carefully, understand the exam pattern thoroughly (no negative marking means attempt everything), prepare Paper I and Paper II with appropriate weightage, and practice extensively with previous year papers and mock tests.

Your preparation should begin now, regardless of when your target examination session is scheduled. Download the official syllabus, create a realistic study plan, and maintain consistent daily effort over months rather than intensive cramming in the final weeks. The investment you make in UGC NET preparation pays dividends throughout your academic career, opening doors to teaching positions, research opportunities, and intellectual growth. Start your journey today, stay disciplined in your preparation, and approach the examination with confidence knowing that lakhs of successful candidates before you have walked this same path to academic careers.

If you want more detailed information on this topic, please visit this blog on LawSikho.

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack